What happened? What are the next steps?

The YNG token report for Q4 2025. What happened in a 2025 full of news? What are the next steps to take? What happened in the last quarter? What were all the goals achieved in 2025? What awaits us in 2026, a decisive year for our future? How many YNG tokens were issued, bought, and sold, and what are the next steps to take?

Young Platform’s 2026

2025 was not just the year of the breakthrough we promised: it was the year in which we redefined our horizon. Twelve months ago, our roadmap was an ambitious outline; today, it has become the backbone of an ecosystem unparalleled in Italy. We did not limit ourselves to following a pre-established path; we chose to evolve at the pace the market requires.

As Peter Thiel teaches in the famous Zero to One, true progress does not lie in copying what exists, but in going from zero to one, creating something entirely new. Aiming high allowed us, despite missing a few intermediate targets, to reach an unimaginable position compared to the start.

The most radical evolution concerns the payment account and the debit card. Officially released in November for the Platinum Club and contest winners, the rollout will begin for the other Clubs in the second week of February.

What will you find in this Report? As the title suggests, the protagonist is the Young token (YNG). After years of construction, 2025 marked its consecration. The listing on Uniswap sparked the most explosive expansion phase in its history.

And then? Much more: from the contests that accompanied us to the launch of the card, to the birth of a new Club, today the privileged gateway to our ecosystem. Finally, an institutional milestone: the official filing of the MiCA license application. You will find the details of this journey and the next strategic steps in the Q4 2025 Quarterly Report. As always, the most exclusive content is reserved for Club members.

Account and card: here we go!

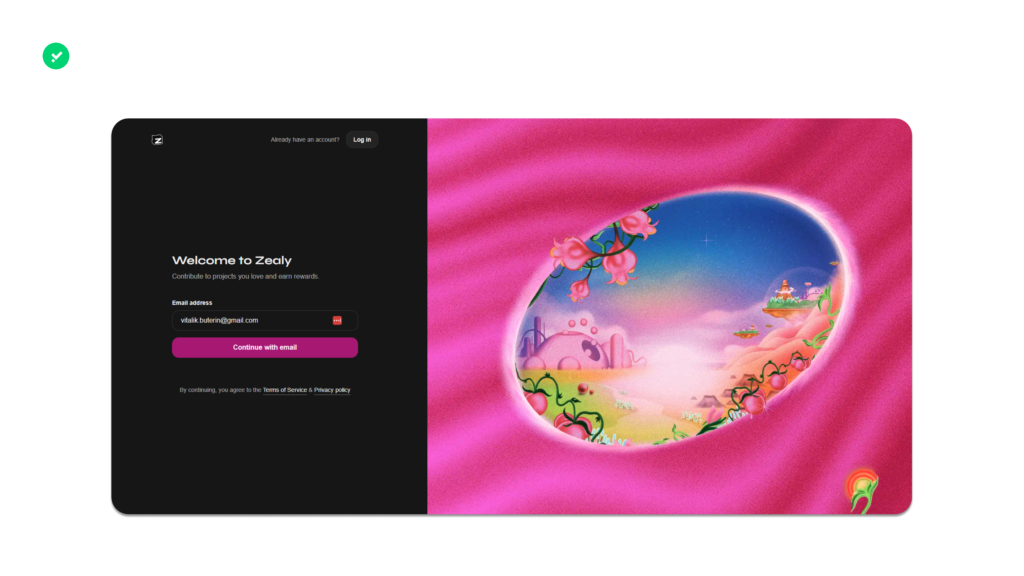

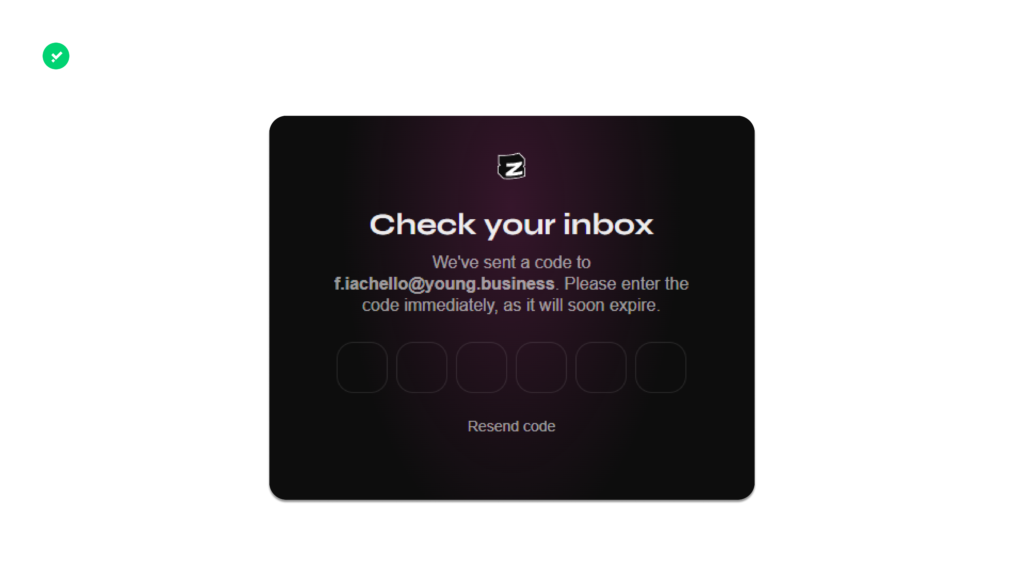

The first chapter of this report should be dedicated to the functionality that consumed nearly all of our energy in 2025. If you follow us on Discord, you know the path was anything but downhill: between supplier delays, legal complexities, and notably frustrating technical bugs—such as entire batches of cards with non-functioning contactless—the road was uphill.

We are currently opening access to the other Clubs gradually and expect to make the functionality public to everyone between mid and late February. Why not immediately? A progressive release allows us to identify bugs in a controlled manner without overloading the infrastructure, ensuring the stability ofthe other sections of the app.

We already know what you are asking yourselves: “When are Apple and Google Pay arriving?” or “How will we distinguish ourselves from competitors?” At the moment, the product is in what we define as Layer 0 (the basic version), but we already have a defined roadmap for future integrations. Some of these answers and technical previews are reserved for the Club version of this report. If you are not yet a part of it, the ideal starting point is the new Club Essential.

Join the Club Essential

MiCA: formal filing deposited

2025 concludes with the achievement of a fundamental regulatory objective, confirming our position as a leader in the regulated market. We are proud to announce that, following extensive preparatory work across all areas of the company, we formally filed the MiCA license on December 5, 2025, and are currently awaiting responses from the competent Supervisory Authorities. This passage marks the natural closure of a path begun months ago. It reaffirms our commitment to operate within the most advanced regulatory framework in Europe, with transparency and investor protection as top priorities.

It is important to note that, under the transitional regime provided by Italian legislation, our operations continue withoutinterruption and in full compliance. For you, this means you can continue to use every platform service with maximum peace of mind, without taking any action, and with the assurance that your assets are managed in accordance with the highest security standards. We will keep you constantly updated on the outcome of the procedure, proud to have honoured our commitments to our community, and ready to inaugurate 2026 under the sign of full European compliance.

In parallel with the MiCA path, work continues on the functionality dedicated to Futures, which is closely linked to it. Technical development is complete, and the service, along with other platform features, has been fully documented in the MiCA dossier submitted to the authorities. We are therefore awaiting the relevant response to define the final operational framework. Committed to our principle of maximum user protection, we are managing this passage with due caution to launch the service only when every aspect of compliance is fully aligned with the required standards.

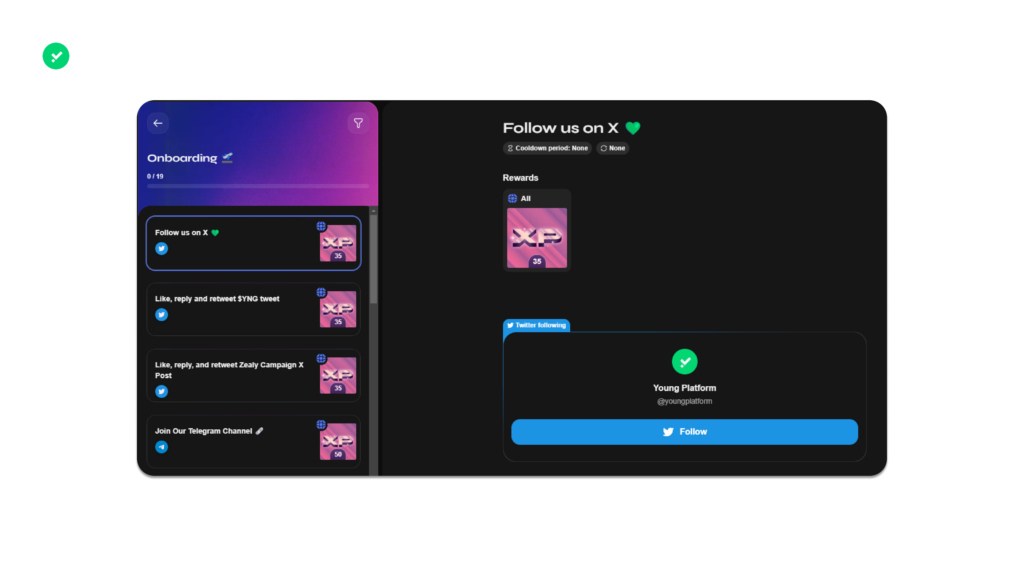

Club Essential: The gateway to the ecosystem

The launch of this new level in Q3 2025 is driven by an objective observation: the success of the YNG token. The year-over-year price appreciation is a positive signal for the health of the ecosystem, but it has made entry into OGs Clubs much more expensive. Despite our dynamic rebalancing mechanism, the Bronze Club threshold at times approached €1,000, creating an obstacle for new users.

The Club Essential is our answer: an entry threshold of 130 YNG that allows anyone to start getting serious without having to wait to reach higher levels.

Essential advantages:

- Trading: 5% discount on commissions.

- Staking: +1% additional APY.

- Cashback: 0.10% on card purchases.

- Operations: 2 activatable Smart Trades.

- Information: access to market reports and the full quarterly report

Consider Essential as a starting point, not a destination. It is the perfect way to test the advantages of the Young Platform world with a limited commitment. Once the benefits have been tested in your daily operations, the transition to the “OG” Clubs (Bronze, Silver, Gold, and Platinum) will be the natural next step for those seeking exponentially higher bonuses, discounts, and cashback.

For all other levels, the 130 YNG required are not a cost; they are simply locked on the platform and remain your property.

Strategic events and the future of Young Group

If we had to choose a keyword to describe a part of Young Platform’s 2026 vision, it would undoubtedly be “presence in the real world.” In the past, we organised live initiatives sporadically, but this year we decided to change our approach by moving to a structured, recurring plan. We are deeply aware that everything we have built is owed to our community, and we feel compelled to give back something tangible, cementing a relationship that, too often in the crypto world, remains confined behind a screen.

Our strategy is articulated in two main directions that aim for maximum inclusivity and, at the same time, the valorisation of our most loyal supporters. On one hand, we are organising informal meet-ups open to all, designed to meet, discuss the market and get to know each other without filters. On the other hand, we are designing a series of exclusive events for Club members and selected investors.

We want Club membership to be a tangible advantage that lets you break the fourth wall and be directly involved in our daily work. Putting our faces in it is not just a statement but an act of responsibility: each of us, from management to the technical team, wants to meet with you to show you the commitment and passionwe put into building the Young ecosystem. Furthermore, making the Clubs increasingly attractive through human contact is our priority, as we believe trust is built by looking into each other’s eyes and sharing a vision of a more accessible and transparent financial future.

I concorsi: “The Reveal”

The saga of Young Platform’s contests was one of the main engines of our 2025, transforming into a real narrative journey that involved the community well beyond the simple reward aspect. Everything started with The Box, the chapter dedicated to addressing financial prejudices, followed by The Unbox. This crucial stage served as a strategic bridge to the launch of the account andcard. The success of the latter was extraordinary: thanks to the Boost Holder mechanism, which rewarded holding YNG with bonus gems, platform activity recorded participation peaks comparable to the market’s moments of maximum euphoria. This commitment translated into a performance of economic significance, with a total trading volume of 19.7 million euros, representing an 8,000% increase from Q3 2024.

On December 9, 2025, we inaugurated the last and most ambitious episode of this trilogy: The Reveal. If the previous chapters prepared the ground, this new phase represents the “Revelation” of reality beyond appearances, with the richest prize pool in our history. For this contest, which ends on March 10, 2026, we decided to refine the game mechanics based on experience. The structure is divided into two parallel competitions: the Championship, based on a general ranking that rewards consistency with iconic prizes such as a Rolex Submariner or a KTM 125 Duke motorcycle, and the Tournaments, six bi-weekly mini-challenges that allow a much wider range of participants to win rewards through random draws.

The real innovation of The Reveal lies in democratising the system. Analysing the Unbox data, we found that those with greater economic availability held a disproportionate number of tickets. To resolve this imbalance, we introduced a Tier system for the unlocking of the lucky tickets: now, the more gems accumulate, the more “expensive” it becomes to obtain new ones. This mechanism in bands also allows those with fewer gems to compete, making even a single mission sufficient to participate in prize extraction. In this way, The Reveal is not just a contest but the culmination of a path of transparency that remains very high toward the ecosystem and the token YNG, which continues to benefit from demand generated by the missions and the advantages reserved for holders.

Young Platform Pro

Parallel to the expansion of our banking services, we have continued to refine the operational core for market professionals. Young Platform Pro has undergone a profound transformation. We adopted the analogy of surgical instrumentation: just as a surgeon needs highly precise instruments to operate safely, an expert trader requires a platform that guarantees instantaneous reactivity, granular control, and absolute operational continuity.

The interface has been optimised in line with international standards for accessibility and visual comfort, reducing fatigue during night sessions and maximising information density on modern monitors. The real revolution, however, lies in the total customisation of the work environment: thanks to a modular tab system, each user can now build their own ideal setup, with layouts and TradingView graphic analyses automatically synchronising in the cloud. This flexibility is now complete thanks to the integration of the new mobile-responsive version, which makes the full power of Young Platform Pro accessible directly in the smartphone browser. This means being able to switch from desktop to mobile without any discontinuity, with indicators, trendlines, and graphic studies saved on our servers.

We have also radically enhanced the order panel to deliver unprecedented execution speed, introducing percentage selectors for rapid capital allocation and total flexibility in calculating amounts, now settable in the base currency of the pair. Under the hood, the integration of API v4 has reduced latency and improved stability, enabling today’s systems to meet the needs of those automating their strategies or requiring real-time data flows. In summary, Young Platform Pro is now a mature, high-performance trading environment designed for those who take the market seriously and professionally.

As always, we have chosen to reserve the most strategic analyses and the most sensitive data solely for our Club members. They are the true protagonists of our ecosystem and deserve unprecedented transparency into the decisions that shape its future.

For this reason, in the report version reserved for Club members, you will find:

- News about the Young Platform payment account and debit card;

- Exclusive Club data: updated member numbers and an analysis of the impact of their purchases on token performance;

- A look at the future roadmap: our strategies and plans for upcoming listings on other centralised exchanges.

These strategic insights are exclusive to those who serve as protagonists in the Young Platform ecosystem and want to deeply understand the levers that will drive future growth. Your support as a Club member is and remains our greatest resource. We appreciate your trust and invite you to continue following us in this exciting chapter of our journey.

Information regarding the YNG Token is for informational purposes only. The Token does not represent a financial instrument. The purchase and use of the YNG Token involve risks and must be carefully evaluated. This does not constitute a solicitation for investment, nor a public offering under Italian Legislative Decree no. 58/1998.

Join a Club!